The enduring importance of a personal library: exploring the archive of longings

The Library is unlimited and cyclical—Jorge Luis Borges

American writer Susan Sontag (1933-2004) in 1972 (Jean-Regis Rouston/Roger Viollet/Getty Images).

Note: While this essay aimed to cover a wide range of ideas, it doesn’t capture everything I initially set out to explore. In true Kayla fashion, I took on a project far larger than I had time to fully explore for a final seminar paper because of what it means to me and my understanding of community. The constraints of time and the broad nature of the topics I wanted to engage with have limited the direction of the piece (for now). It’s unfinished and messy, but I need to move on from it for a while. I’m okay with sharing unfinished works because they are part of the sometimes tedious and meticulous writing process I love but can also sometimes drive me to madness. In the spirit of Indigenous practices that emphasize wholeness and accessibility, this version is a beginning. I hope to refine it further in the future.

Introduction

"My library is an archive of longings," Susan Sontag once said—a phrase that captures something essential about the personal library as a space of questioning and nourishment. In this context, a personal library refers to a collection of books and resources curated by an individual for personal learning or pleasure. Longing doesn’t necessarily need to be a painful or empty experience. It can be nurturing. It can be a place that sparks introspection and self-inquiry. It can lead us to action, to seek out new connections, growth, or knowledge.

My life has been one of longing. During my childhood, which was spent mostly alone, I sought to learn about the world. I wanted to see what was beyond the suburbs of Whalley and to, as Sylvia Plath once said in her Unabridged Journals, “feel all the shades, tones and variations of mental and physical experience possible in my life.” I was young and didn’t yet have the agency to do these things myself, so I reached for books. There, I realized the role a library could have in our lives.

There is a sense of safety in exploring books, where one can try out new ideas, passions, and facts. In Healing With Books: A Literature Review of Bibliotherapy Used With Children and Youth Who Have Experienced Trauma, the authors introduce bibliotherapy as a method to help children and teens heal and develop coping skills after trauma. They explain that "the use of literature and identifying how to live more effectively through the characters and problems featured in a book enables children and youth to increase their insight and understanding of the themes and experiences as it relates to their own lives." A library—whether personal or public—is essential to this development. It was for me.

In Packing My Library: An Elegy and Ten Digressions, Alberto Manguel reflects on the libraries of his childhood, noting that there were “only a few books that a serious bibliophile would have found worthy” (3). But what if the value of a personal library goes beyond the judgments of a “serious bibliophile”? What if worthiness is not determined by external standards but by the individual choices and needs of each individual curator?

“The books themselves, I felt, belonged to me, were part of who I was,” Manguel continues (4). If we consider these books not as possessions but as an addition to our lives, it feels as though we honour both the spirit of the books and our relationship with them. “We read to ask questions,” he continues, emphasizing the role of reading as an ongoing inquiry (41). Next to that, in the margins of my copy, I wrote: “I suppose this is why I like to have books I haven’t read in my collection. I like to be in progress; I like the journey. I don’t always want to reach the destination.” This sentiment resonates with Manguel’s view that our libraries are “never the definitive story” (8). Like us, they are works in progress—constantly evolving with each new reading and each question we ask.

My current library is still relatively new. The one I built over the first two decades of my life, I gave away in an attempt to embrace the minimalism trend of the 2010s. But minimalism, it turns out, wasn’t for me. I realized I needed a space where books lived alongside me to help stimulate my curious mind. When I turned 30, I began to rebuild my collection. Now, at nearly 35, my library has grown to 686 (ten I bought just to write this essay). I’m quickly running out of space to house them, and as I envision the future I want, I picture a home with room for a sizable library, one that involves books that both the future husband and children I long for want to read.

If we are to define a library, let us reach to Unpacking the Personal Library: The Public and Private Life of Books by Jason Camlot and Jeffrey Weingarten, where they frame libraries as “sites of interpretation” that reveal insights about “collecting, arranging, and circulating knowledge” (Camlot and Weingarten 1). In their definition, “a library is a collection of books (to one degree or another) for the use of one or more persons. In the case of personal libraries, the collection can paint ‘the broadest picture of what and (sometimes) when ideas were being read, internalized, and absorbed’ into an owner’s life and work” (Camlot and Weingarten 1).

A library isn’t bound by the size of its collection; it can exist on a single shelf in someone’s space. In my world, I think of Vanessa Prescott’s collection of books on herbal medicine for her practice, Ryan Kerpan’s small selection of books on sign painting nestled in his sign shop, a student’s backpack carrying a stack of books for an upcoming paper, or the line-up of books being sold off the concrete near the Commercial Drive SkyTrain station. I think of the small, tucked-away library in the cabin of Raincoast Conservation's research sailboat Achiever, which I reached to constantly while sailing around the Gulf Islands. Each of these examples—whether a personal library of reference materials, a mobile collection, or a spontaneous community library on the street—demonstrates how libraries can exist in unexpected forms and places.

As my friend Fern DiRossi-Bird shared with me, "Borrowing books from public libraries can also be viewed as being part of your collection, just in a more fleeting way." It’s the same excitement felt at the Scholastic book fairs of the ‘90s or when one first walks into an Airbnb and inspects the selection of books—the thrill of discovery is as much about the experience itself, no matter how limited or fleeting their physical boundaries may seem.

While public libraries are also near and dear to me, my focus here lies only on the personal. What I wanted most was a way to understand a habit that some of us participate in. Here, I examine how personal libraries serve as both a tool and a catalyst for action, not simply as a physical space but as a space for self-directed learning and liberation. From its historical roots to the act of curation and its role in our daily lives, I look at how libraries are shaped throughout a lifetime and argue that they are not static entities but rather ever-evolving parts of our lives.

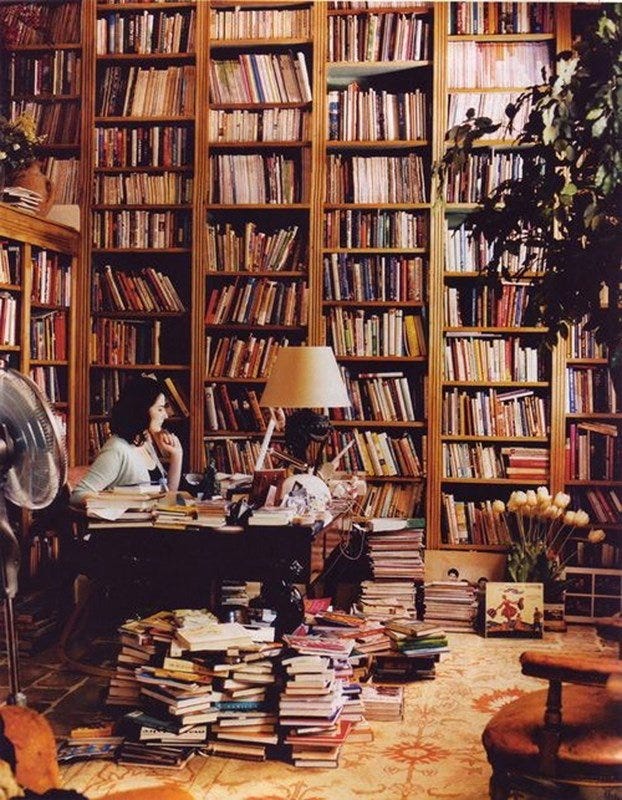

Food critic Nigella Lawson's home library houses over 6000 cookery books on floor-to-ceiling shelves.

Defining the Library

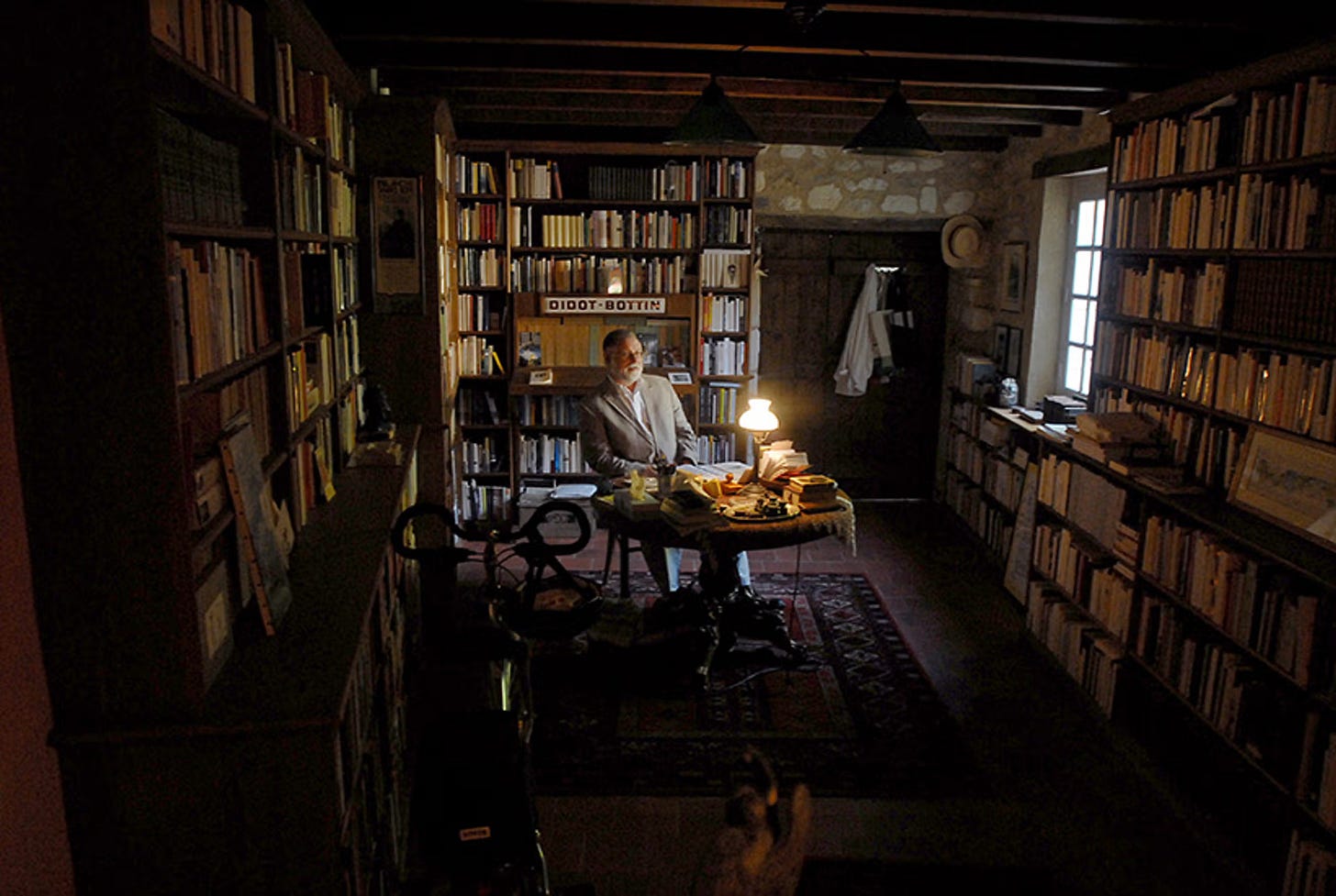

Manguel describes his library as his “private domain” (Manguel 4), a space where his personal reflections and intellectual explorations unfold. He opens Packing My Library: An Elegy and Ten Digressions by reflecting on his last library in France, located south of the Loire Valley. He chose the house partly because a nearby barn was spacious enough to house his collection of thirty-five thousand books. Manguel organized his library based on his own personal requirements and system of classification. For him, the library was “an utterly private space that both enclosed and mirrored [him]” (4). He further expresses, “I’ve often felt that my library explained who I was, gave me a shifting self that transformed itself constantly throughout the years” (Manguel 5).

For me, a library is a space of remembrance, a place to store the ideas and stories I’ve encountered but cannot fully retain in my mind. It is, of course, a collection carefully curated to meet my needs as an artist, scholar, and writer. My desire to build a library can be traced along several paths: 1) it serves as a memory palace, 2) it acts as a refuge, and 3) it functions as a toolkit that inspires me into action. In this sense, the library is not simply a physical repository of books but a space that also preserves fragments of my intellectual and emotional life.

In his posthumous collection Everything in Its Place: First Loves and Last Tales, Oliver Sacks reflects on libraries as his favourite places, among his first memories (41). For Sacks, they were spaces for active engagement and self-directed discovery. He “disliked school, sitting in classes, receiving information”—it felt too passive (41). I, too, often felt unstimulated in school. Diagnosed with ADHD at four years old, I wanted to be in motion, preferring to engage with what I was learning rather than playing memory games and sitting still. Sacks describes how he experienced the kind of freedom and agency that school could not offer: “I was a good learner, and in the Willesden library—and all the libraries that came later—I roamed the shelves and stacks, had the freedom to select whatever I wanted, to follow paths that fascinated, to become myself” (41; emphasis mine).

Toni Morrison’s library (Brown Harris Stevens).

The History of the Library

Historically, owning a library was a marker of intellectual depth and social status. It was also “a display of wealth, power and taste” (Pettegree and der Weduwen 181). A personal library signified cultural capital—a way of displaying one’s erudition, one’s place in the world of ideas. In The Library: A Fragile History, Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen draw on their experiences working in over 300 libraries and archives to offer a comprehensive understanding of the scale and significance of these special spaces.

Pettegree and der Weduwen trace the evolution of libraries, from the ancient Library of Alexandria to the destruction of the Jaffna Library, while also examining the shift toward digital reading platforms. Despite these transitions, they remain optimistic about the future of libraries (414). However, as they point out, capturing the full history of libraries is a complex task, for "the evolution of the library is far from linear" (4). The definition of what constitutes a library, they argue, is something each generation must continually redefine. For the purposes of this study, the focus will be on the personal library.

The role of personal libraries in history was most pronounced during the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods when the ownership of books was synonymous with the rise of humanism. As Pettegree and der Weduwen write, "the importance attached to books in this scholarly programme was most obvious in the emergence of private studies” (61). The act of creating a space dedicated to literary activity was considered the highest form of devotion to letters and "the apex of civility" (61).

My focus is not on books as objects in the possessive capitalist sense, nor am I concerned with their aesthetic value or historic role as symbols of power for the elite, though it is important to consider. Instead, I am interested in the history of using books as a toolkit—resources for learning and a medium for conversation.

“Researching the source of artworks should include an examination of the reading habits of artists,” writes Anne H. Young in Preserving Artists’ Personal Libraries: Providing Insights into the Creative Process. Young questions the absence of scholarly investigation into these artists' libraries and wonders, “What kind of books did an artist read and enjoy [...] as the encounter point” (340). She explains that “works of art are not produced in a vacuum” and that every work of art is surrounded by “what might be called its artistic field,” which is the creative which is the ecosystem that an artist interacts with, which in turn influences and informs their work (341).

Artists, writers, and thinkers have long been central to the significance of these libraries. Libraries once owned by figures such as Jacques Derrida, Edith Wharton, and James Joyce have been preserved by academic institutions because they can “give the scholarly community valuable insights into the writer’s minds and their work” (Young 339). When Toni Morrison’s collection of over 1,200 books went up for sale in 2020, it sparked widespread attention and interest. Similarly, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s library, consisting of just a few books, influenced his creation of over 600 paintings and 1,500 drawings (Make Art Not Content 00:23).

The Virginia Woolf Library, housed in the Terrell Library at Washington State University in Pullman, Washington, is one such example that offers insight into a library used as a tool that facilitated work and creative processes. As Camlot and Weingarten explain, “These resources are wonderful aids, but a visit to the library more potently provokes ideas and discloses connections” (133). The collection includes almost six thousand titles in nearly ten thousand volumes, though “many books were given away or lost to mildew” because “the Woolfs’ books were always meant to be read, not protected” (133). While showing signs of use, these books are essential in helping us construct narratives about Woolf’s life and milieu “and inform interpretations of an author’s work” (133). For example, the poetry books Woolf owned shed light on her “vexed attitude toward the form, an attitude advantageous to her art” (134), which has helped scholars understand her creative vision.

As Pettegree and der Weduwen explain in their introduction, “We should not romanticize libraries, not least because their owners seldom did. For much of their long history, libraries were primarily an intellectual resource and a financial asset” (14). The true value of a library, especially a personal one, lies not in its ability to impress others but in its capacity to serve as a space of connection. Wealthy individuals may have used libraries as symbols of their social standing, but for the majority of us, they were and are functional tools. Despite the grand facades of some private collections, we must remember that “the numberless collections of books assembled in private homes did every bit as much to sustain a vibrant book culture as institutional libraries” (15).

A photo of me in front of part of my home library, May 2022.

The Act of Curation: Building a Personal Library

When we think about creating a personal library, curation becomes central to the process. Curation isn't simply about indiscriminately acquiring things or passively collecting; it involves a mindful, intentional selection of items that reflect personal meaning, purpose, and engagement. I see it as an act of careful stewardship, where each addition to one’s library is chosen for how it fits into a larger narrative of one's life.

The idea of curation has evolved beyond its original art-world context, where curators were once the arbiters of what was considered significant or worthy. As the Oxford English Dictionary notes, to curate is “to select, organize, and look after the items in a collection or exhibition” (OED). In Curationism: How Curating Took Over the Art World and Everything Else, David Balzer discusses the concept of curation has expanded far beyond the world of galleries and museums into every corner of life: "We ‘curate’ in relation to ourselves, using the term to refer to any number of things we do and consume on a daily basis" (17). Balzer highlights “the increasing use of the noun curator and the verb to curate outside the art world,” a shift so widespread that, on any given day, scrolling through Instagram, you can see people curating playlists, personal styles, and dinner parties (8).

But, what does this mean for us when building a personal library specifically? The root of the word "curate" is telling. Derived from the Latin cura, meaning care, it implies that the curator is more than a neutral organizer. A curator—or curatore—is essentially a "caretaker," someone who manages a collection and cares for it, nurturing it over time (Etymonline). Building a personal library is about understanding the responsibility of selecting the resources that aid in shaping who we are and how we show up in the world. Good curation also involves diversification: while we often reach for what we know, it is important to open ourselves to new ideas. By aligning our choices with our values, challenging our biases, and committing to a thoughtful and ongoing process of discovery, we can be surprised and inspired whenever we choose to pick up a book.

I’m careful to differentiate between curating for utility and curating to define one’s identity or for display. While books can certainly inform and shape who we are, their role in a library doesn’t always need to be flattened to symbols of taste or identity. I try to avoid the trap of being a purist. I believe people can collect in whatever way feels meaningful to them. This is more of an inviting and accessible approach—a quiet, contemplative, utilitarian process. Though my identity is, in part, shaped by the books I read and the resources I interact with, it’s important to note that they do not strictly define it. As Balzer suggests, “who we are is expressed by what we like and collect," but, as Toronto-based broadcaster and researcher Jesse Hirsh notes later in the book, “we don’t always collect for the same reasons” (131).

As I write this essay, I realize that I am, in fact, curating my own perspective on personal libraries. In that spirit, I will curate a list of some famous personal libraries that I find fascinating. Susan Sontag’s Manhattan library, with its 15,000 books, was more than an intellectual resource; it was a testament to her lifelong engagement with a wide array of subjects, including art, architecture, dance, philosophy, psychiatry, photography, opera, theatre, and the histories of medicine and religion. Then there are the libraries of Virginia and Leonard Woolf, the Dickinson library, Nigella Lawson’s library, and Julia Child’s Massachusetts library. Finally, there’s my own childhood library, which resides now only in my memory, where my mum once said, “You used to organize your books by colour, then alphabetically.” Organizing books by colour is no longer my preference, but I do believe a personal system is necessary to the curating process.

My current library has been a means of slow, deliberate curation too—an ongoing process that mirrors my interests and presence in the world. Take, for example, my copy of Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space. I didn’t just pick up any edition; I specifically sought out the 1964 translation, with the cover designed by Wladislaw Finne. While a cover might not always dictate my choice, Finne’s design carries a particular resonance for me. A Russian émigré whose family fled the Revolution, his design connects to my interest in Russian culture and art history. Other times, my choice of books is driven by the content itself. Take, for example, the revised and updated 2019 edition of Halfbreed by Maria Campbell, originally published in 1973 by McClelland and Stewart. Recently, SFU’s Alix Shield and Deanna Reder (Cree-Metis) uncovered two missing typewritten pages from Campbell’s lost manuscript—pages that had been removed under pressure from her publisher, who insisted she omit passages about her rape by an RCMP officer to make the book more commercially viable (Reder and Shield 44). With these pages restored, Campbell said she finally felt the book was finished (Goodyear).

The taxonomy of my collection reflects my deliberate effort to organize and categorize texts in a way that speaks to my varied interests, as well as my professional and creative work. There’s a shelf dedicated to BIPOC authors, two shelves focused on Indigenous history, literature, and poetry, and a selection of contemporary thinkers and poets. As a journalist, some of my writing focuses on food and music writing. For that, I’ve carved out a section for books by food writers, alongside cookbooks in my kitchen and two shelves filled with music history books and biographies. Another shelf is classified by my love for the outdoors, featuring works on conservation, along with field guides for sailing, backpacking, and weather identification. I also have a section devoted to the arts, including books on photography, textile mending and repair, and typography and design. While I won’t list every area my library covers for fear of overwhelming the reader, I do want to underscore the significance of these resources as points of departure in engaging with the world beyond the page.

While curation is intentional and reflective, the act of collecting can often be driven by impulse or desire without much thought to purpose. This distinction makes me wonder: can one truly curate without collecting? And how do we avoid letting the library become an unchecked accumulation rather than a curated collection with meaning? For me, my library is not only an archive of books—it functions as a tool, a space for discovery and reference. I see it as a resource that supports my intellectual and personal growth and serves both as a source of inspiration and a practical means of engaging with the world. But how can a library truly work in one’s home? What is the utility of this space, and how does it function day-to-day?

A print screen of a conversation between my classmate Yelani and me where I recommend books from my collection yet again. If anyone asks me to talk about Dionne Brand, I will no doubt go on forever.

The Space: How a Library Functions in the Home

But a personal library, though seemingly private, is never entirely so. The books I gather don’t just live on my shelves—they serve as a resource for those who visit my space, for friends and family who borrow them, or simply peruse them while visiting. My library is an offering then, an invitation to share knowledge and ideas beyond my own use. I think of it as a small, accessible archive of thought that extends outward beyond the self.

While writing this essay, for example, I was able to reach for books on my shelves to assist my classmates. When Ben wanted to learn more about the ethical dilemma surrounding authorial intention and the right to privacy regarding diaries and manuscripts, I pulled out the first edition of Susan Sontag’s Reborn: Journals and Notebooks. I recalled how her son discussed the "literary dangers or moral hazards" of releasing his mother's journals in the preface and sent him a photo (Sontag vii). Meanwhile, my other classmate, Mathuri, needed help citing Toni Morrison’s concept of “rememory.” I reached for my copy of Beloved and photographed page 43, where Morrison first introduces the idea. This is how I want my library to be used.

In the practical, creative, and deeply personal role, my library reaches into my daily and creative life nonstop—beyond words, beyond theory—helping me with design and typography, cooking beautiful meals for my community, mending and repairing clothes, personal development and healing from trauma, or planning new artistic projects. In our hyper-individualistic and capitalist society, this feels like a small act of resistance—an affirmation of connection, creativity, and resourcefulness that goes against the grain of consumerism and disposability.

Knowledge is rooted in relationality, and the stories we hold are like libraries in themselves. In Indigenous Healing: Exploring Traditional Paths, Leroy Little Bear emphasizes this point, stating, “Knowledge is represented in the Aboriginal context as multiple and diverse processes and includes our ways of knowing.” For Indigenous communities, the source of knowledge lies in “sensory experiences,” much like the act of visiting or sharing knowledge within a personal library, which plays a vital role in nurturing the health of our communities (65). I think of spaces like the Vancouver Black Library and Out on the Shelves Library, which have cultivated safe spaces around BIPOC and queer identities that can help us reach toward belonging, empowerment, and connection.

For the sake of space and time, I’ll leave you with a few questions: How does your library function in relation to community or collaboration? Do you share books with others, host reading groups, or engage in discussions about your collection? Are there ways in which your library interacts with wider cultural or intellectual communities (e.g., book clubs, academic circles, or public libraries)? Do you consider how others might engage with your collection, whether through lending, gifting books, or sharing annotations and thoughts in marginalia?

A photo of all the books I owned in 2019 as I tried to rebuild my collection. The Kerouac has been removed, but most of those are still a part of my current collection.

Conclusion: The Evolution of One’s Library Over a Lifetime

My library is ever-evolving. At times, books have helped me find ways to explore and share who I am. Now that I’m in my 30s, I have more certainty and knowing about my identity. Pieces that were once permanent residents on my shelf have been re-homed. In my twenties, when I saw writers like Kerouac and Bukowski on the shelf of a man I was interested in, it would intensify my attraction. Now, their portrayals of women feel objectifying and reductive, steeped in masculinity that, at times, feels self-indulgent and misogynistic. While I still find Kerouac's depiction of life "on the road" poetic, I've since discovered other writers who explore similar themes with depth and nuance that’s more resonant.

I’ve recently begun to curate a new corner of books as a future resource for the children in my life. Whether my own or the children of friends, I want my library to be a place where young minds can encounter and experience new worlds and thinking. One day, I hope they’ll pull a book from the shelf and learn about the colour blue. Or perhaps they’ll explore the art of sashiko. Maybe even the history of pigmentation and colours or the stories of the disappearing and reappearing buffalo in the prairies.

When I think about what books can do for children, I think of my own journey. It may sound familiar, but books were my escape, my way out of generational trauma. As a child, when my parents fought, I would hide behind the door of my room, reading by the dim light that leaked through the crack. In those moments, books allowed me to imagine a future beyond survival, a future where I could chart a different course for myself and my family—not necessarily one that was "better," but one that was fuller, more expansive than merely getting by. I recognize the privilege in this, knowing that my ancestors and even my parents were often confined to the struggle of survival itself.

As Weingarten writes in the conclusion of Unpacking the Personal Library, “To build your own library is always a remarkable privilege.” The time to read, the financial means to afford books, and the space to house them are all things not everyone has the luxury of. But it also means something else: education and the freedom to engage with knowledge in ways that many, throughout history and across the globe, have not had access to. Just as Toni Morrison once told her students, “If you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else.” This calls for using one's privilege, including access to books and education, to uplift others. In the context of libraries, this means considering how we share knowledge, how we curate our collections, and how we contribute to the intellectual and cultural freedom of those around us.

Argentine-born writer Alberto Manguel pictured Sept. 11, 2007, in his house of Mondion near the city of Châtellerault, France. (Alain Jocard/AFP/Getty Images)

Until next time,

Kay

“So Matilda’s strong young mind continued to grow, nurtured by the voices of all those authors who had sent their books out into the world like ships on the sea. These books gave Matilda a hopeful and comforting message: You are not alone.” ― Roald Dahl, Matilda”

Of interest for the work done by librarians on Convers Francis' Library.

Carlson, Nell K. and Russell Pollard, "Reconstructing the Library of Convers Francis" in Graham, M. Patrick (Matt Patrick), ed. Preserving the Past & Engaging the Future: Theology & Religion in American Special Collections, pp.65- 90. Chicago, Illinois: Atla Open Press, 2021.

This is so beautiful, Kayla